Part 1: Gastroenterologists Can Often Determine

What Is AND What Isn't Wrong With You

This article describes one of six things I've learned about gastroenterologists through my personal experiences and through research. I'd suggest you set your expectations accordingly, but your experiences might vary from mine.

For the complete series of articles, see Six Things You Should Know About Gastroenterologists.

Gastroenterologists Are Diagnosticians, First and Foremost

If you have digestive complaints, gastroenterologists can very possibly diagnose what's wrong with you. If you have a disease or disorder that they can diagnose, you want to know about it.

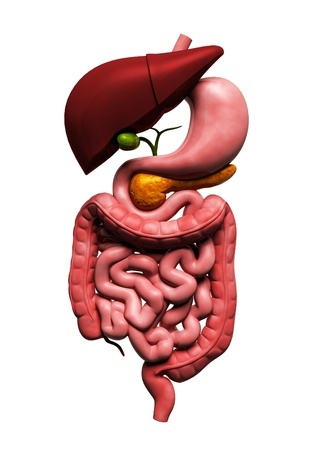

Although gastroenterologists use various techniques to examine the digestive organs, they most commonly perform the colonoscopy and endoscopy procedures. With the latter, they typically perform an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy.

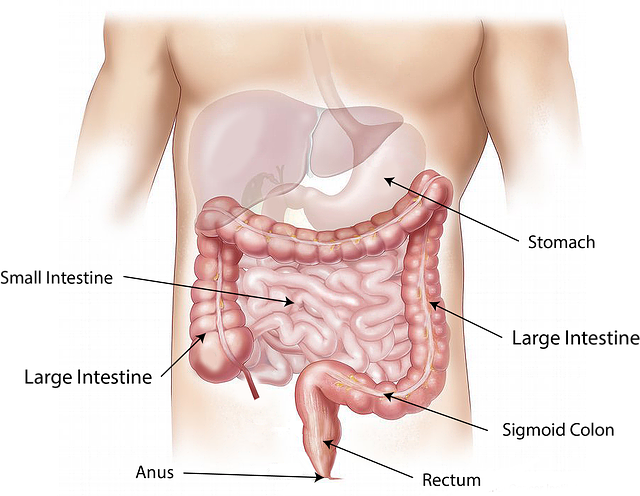

A colonoscopy examines the large intestine for disease, most commonly colorectal cancer, but also ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, among other diseases.

An upper GI endoscopy examines the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (the upper portion of the small intestine). Gastroenterologists can look for inflammation, bleeding, ulcers, tumors, and other tissue changes.

With both procedures, gastroenterologists can take small samples of tissue, called biopsies, which can aid in their diagnosis of digestive diseases.

List of Common Illnesses That Gastroenterologists Diagnose and Treat

According to the American Gastroenterological Association, gastroenterologists can diagnose and treat the following common illnesses:

- Colorectal cancer

- Celiac disease and food intolerances

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

- Heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Chronic vomiting and gastroparesis (delayed gastric emptying)

- Peptic ulcer disease and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

- GI infections caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoa

- Diverticulitis, diverticulosis, and ischemic bowel disease

- Functional illness, such as constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, belching, and flatulence

- Viral hepatitis

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Cirrhosis

- Acute and chronic pancreatitis

- Gallbladder disease

- Appendicitis

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Obesity

As you can see, gastroenterologists cover a lot of ground in the body.

What's Missing From This List of Common Illnesses?

Despite the long list of common illnesses that gastroenterologists address, in my opinion, some key illnesses are missing from this list. Here are some that come to mind:

- Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (though maybe they lump this illness in with food intolerances)

- Increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut syndrome)

- Hypochlorhydria (low stomach acid)

- Gut dysbiosis (gut microbiome imbalances), including small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

- Histamine intolerance

- Gastritis (inflammation of the lining of the stomach)

I am surprised to see nutritional deficiencies in the list of common illnesses. The three gastroenterologists I have worked with have never mentioned this possibility, much less tested me for any potential deficiencies.

And that is despite knowing that I have a very restricted diet due to my many food intolerances.

It Also Helps to Know What's Not Wrong With You

Here's one of the major benefits of seeking the help of gastroenterologists: They can help you determine what's not wrong with you.

You will probably learn something from every gastroenterology appointment you have and from every test you undergo. Even though you might become frustrated if you don't have answers yet, it helps to know what you don't have.

Here are some examples from my personal experience:

- From my first gastroenterologist, I learned that I did not have Crohn's disease—which I greatly feared might be the case due to my family history.

My uncle was diagnosed with Crohn's disease in his early 20s. This disease disabled him, forcing him to move back home with my grandmother. Unable to work, he received disability payments for many years. After multiple surgeries that removed parts of his intestine, he ended up with a colostomy, which means he defecated into a bag to bypass his damaged colon. He died at the relatively young age of 49.

As you can imagine, it was a tremendous relief to learn that I did not have this dreaded disease. - From my second gastroenterologist five years later, I learned that I did not have the villous atrophy that is characteristic of celiac disease, nor did I have small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

However, I did learn something important months later from reading the report written by the pathologist who examined my endoscopy and colonoscopy biopsies. In his professional opinion, the pathologist wrote, he could not rule out Crohn's disease in my ileum (the lower part of my small intestine).

What?! Might my digestive woes have devolved over time into Crohn's? And why did I learn about this possibility from reading the pathology report and not from my gastroenterologist? My gastroenterologist merely told me that the biopsies of my ileum showed “nonspecific inflammation.” - From my third gastroenterologist 19 months later, I learned that the strange substance I observed in my stool one day (which I had photographed for show-and-tell with my doctor) was not a flatworm—at least not one he had ever seen.

Also, nearly two years since my second colonoscopy and endoscopy, this third gastroenterologist performed these procedures again. There were no signs of anything amiss in my ileum, including no sign of Crohn's! I credit this improvement with everything I have been doing to prevent worse things from happening in my body.

(Unfortunately, as of this writing, I still have gastritis and esophagitis. So I have more healing work to do.)

Despite Their Expert Diagnostic Skills, Gastroenterologists Don't Typically Focus on Addressing the Root Causes of Disease

In my experience, even if gastroenterologists can diagnose you with a disease or disorder that they recognize as valid, they might not be of much help if you are seeking to find and resolve root causes—and if you have an inclination toward natural healing.

For example, perhaps your gastroenterologist confirms a diagnosis of constipation, but conventional testing doesn't reveal an underlying cause such as Crohn's disease or celiac disease. What then? You might get advice to eat more fiber and drink more water. For some people, that works.

But what if that doesn't work, like in my case? Your gastroenterologist is likely to recommend you take MiraLAX, an over-the-counter (OTC) osmotic laxative. Gastroenterologists say you can take it safely, indefinitely.

But something is causing the constipation. With MiraLAX, you are merely treating the symptom of constipation, not uprooting and attempting to heal its cause or causes. I think that's fine to do—temporarily, while you seek the root cause—because you really don't want to get clogged up. Bad bugs can breed in your digestive tract under such conditions.

This points to my biggest problem with conventional medicine: its tendency to treat symptoms, not address root causes. Symptom suppression is not the answer.

Here are two more examples:

- Conventional medicine treats the symptoms of IBS but generally doesn't seek its root causes.

In my opinion, IBS is the diagnosis some of us receive after all other possibilities that conventional doctors consider have been ruled out. Fortunately, some doctors now recognize small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) as one of the root causes of this disorder. However, SIBO itself even has various root causes (such as food poisoning, low stomach acid, previous intestinal surgery, and ileocecal valve dysfunction). - Conventional medicine treats the symptoms of GERD but generally doesn't seek its root causes.

Conventional doctors claim GERD is caused by too much stomach acid backing up into and damaging the esophagus. If that's true, then what's causing the high stomach acid? And how can people with GERD bring their stomach acid production back into balance? Taking an acid blocker is nothing more than a symptom suppression strategy.

Many experts actually believe the opposite to be true, claiming that low stomach acid is what causes GERD, as well as other digestive woes down the line. For example, Jonathan Wright, MD of the Tahoma Clinic in Washington state, has been testing stomach acid in people with heartburn and GERD for over 25 years.

In his book, Why Stomach Acid is Good For You: Natural Relief from Heartburn, Indigestion, Reflux and GERD, Wright explains: “When we carefully test people over age forty who’re having heartburn, indigestion and gas, over 90 percent of the time we find inadequate acid production by the stomach.”

Chris Kresser, MS, LAc, offers an extensive five-part series on GERD and what he refers to as “its mismanagement by the medical establishment.” If you'd like to dive in, start with Part 1, What Everybody Ought To Know (But Doesn’t) About Heartburn & GERD.

Kresser discusses at length the dangers of long-term use of acid blockers to treat GERD. He lists the four primary consequences of these medications: increased bacterial overgrowth, impaired nutrient absorption, decreased resistance to infection, and increased risk of cancer and other diseases.

The reason for these consequences? We need sufficient stomach acid to avoid these dangers, and these acid blockers greatly reduce stomach acid production.

Kresser states that Prilosec and other proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the worst. “Just one of these pills is capable of reducing stomach acid secretion by 90 to 95 percent for the better part of a day. Taking higher or more frequent doses of PPIs, as is often recommended, produces a state of achlorydia (virtually no stomach acid). In a study of ten healthy men aged 22 to 55 years, a 20 or 40 mg dose of Prilosec reduced stomach acid levels to near-zero.”

CeliacFAQ.com home page > Articles > 6 Things You Should Know About Gastroenterologists >

Gastroenterologists Can Often Determine What Is and Isn't Wrong With You